All scientific studies are not created equal.

Each type of scientific study has its uses and value, but when you make decisions on diet, exercise and other behaviors you are literally betting your life.

So it’s important to understand what different kinds of studies can tell us, and what they can’t.

The weakest evidence comes from observational studies. In a retrospective observational study, scientists compare outcomes in different populations or subgroups and compare characteristics of those populations.

They may note differences in outcomes, and then try to identify differences between the two populations that might explain the differing outcomes.

That’s an important and highly beneficial use of these kinds of studies: to generate hypotheses.

But those hypotheses need to be tested. Just because two factors are correlated doesn’t mean there is a causal relationship.

Sometimes the correlation is so strong that causation is highly likely. For cigarette smokers, for example, the incidence of lung cancer is 20-30 times higher than among nonsmokers. If the effect is large enough, an observational or epidemiological study can provide a good guide to decisions.

It would be foolish to think smoking is safe just because a controlled experiment in humans is impractical and unethical.

On the other end of the spectrum from observational studies is a randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial.

- A controlled study is one in which a group that is treated is compared with one that is not, the controls. If the outcomes of the treatment group are significantly better than the control group, it shows that the treatment has value.

- Placebo-controlled means that some kind of intervention is done in each arm of the study. One group gets the pill that is hypothesized to be beneficial, while the other typically gets an identically appearing sugar pill. This is designed to overcome the placebo effect, in which people report feeling better because they think they’ve been treated. To be meaningful, the treatment arm needs to have results that are significantly better than placebo.

- A randomized trial is one in which people are assigned by chance to either the treatment or the control.

- A double-blind study is one in which neither the study subjects or the investigators know who is getting the treatment and who is a control. In addition to guarding against the placebo effect among subjects, this is designed to keep the investigators from imagining improvements in the treatment group.

This kind of study is often called a “gold standard” study. In the best of them, the treatment and control groups will be as identical as possible. You wouldn’t want one to have 60% tobacco smokers while the other has 30%, for example. Ideally, the only relevant difference between the groups will be that one got the treatment while the other didn’t.

It’s also important to have a large enough number (or n) to enable statistical analysis of the likelihood that the result was not due to chance. As you read studies you’ll note that a p value is given, such as p<.05. That means the likelihood that a difference between the groups is due to chance is less than 5%: we’re 95% certain that the outcomes difference is a real one.

The strongest studies also have “hard” or objective endpoints, which are the outcomes being measured. Death or a heart attach are hard endpoints, while subjective measures like “feelings of well-being” are soft endpoints.

One of the big problems in scientific reporting is when headlines say, “Study shows….”

If it’s a gold standard study (randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled), that’s legitimate.

If it’s an observational or epidemiological study, the more accurate headline would be “Study suggests ….” Those studies can only generate hypotheses to be tested in more rigorous gold standard studies.

So why even do these observational studies? They enable identification of promising lines of inquiry at lower cost. They can provide a good starting point.

One final type of study that is relevant for our consideration is animal studies. Because of common metabolic pathways, these also can suggest potential applications in humans.

Like observational studies, animal studies can point to areas for further investigation, but they aren’t definitive. Their major advantage is that with the shorter lifespans of animals and our ability to enforce compliance with the intervention, we’re able to get those preliminary answers in a shorter timeframe. And we don’t need to worry about the placebo effect in animals.

But lots of findings in mice have not borne out in human studies.

So how does this relate to dietary studies, and what should we do about it?

- It’s almost impossible to do a study of free-living humans for any length of time that truly isolates one variable.

- The effects identified in observational studies are typically not large enough to justify confident proclamations. An odds ratio of 20 or 30 meant cigarette smokers were 20-30x more likely than nonsmokers to develop lung cancer. If the odds ratio for developing colon cancer because of nitrates in bacon is 1.1, it’s a lot less clear that bacon is really a problem (see #1).

- The effects of diet accumulate over a lifetime. Even smoking seems to have its carcinogenic effects over a period of years, not weeks or months.

- It’s extremely hard to have a blinded study of diet, at least with normal foods. People know whether they’re eating eggs or pancakes, bacon or okra.

- Eating in a way that is radically different from what our ancestors ate, at least over the last several thousand years, is unlikely to be a prescription for health and vitality.

My main point is that it’s hard to determine precisely the health effects of different eating patterns and habits. It’s even harder when one hypothesis, the diet-heart hypothesis, becomes established and leads to confirmation bias driving out dissent, making it difficult to do and publish research that doesn’t align with prevailing thought.

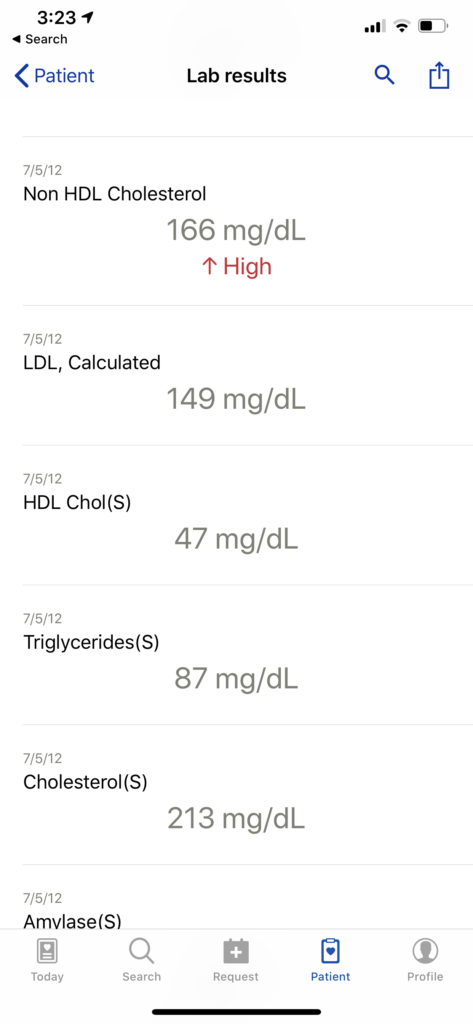

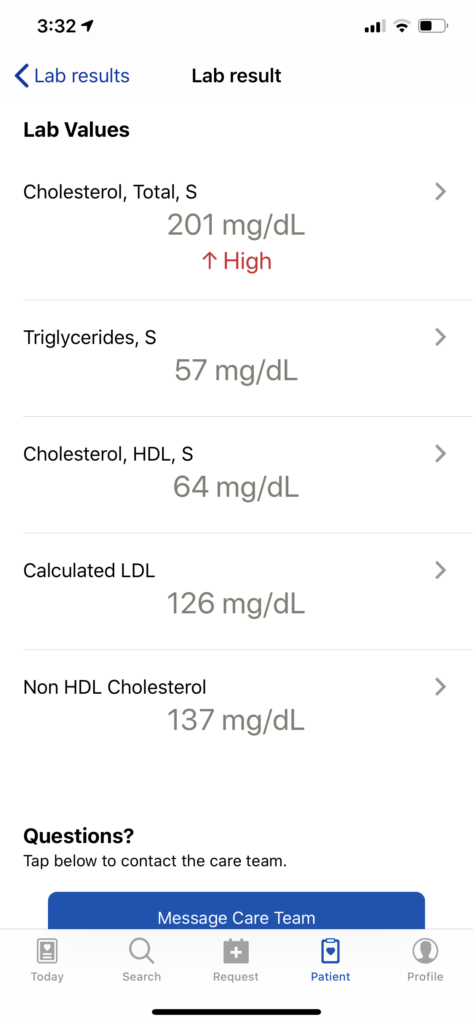

And yet, we each are our own n of 1, and we need to decide what we’re going to eat today. Based on my reading and personal study and experimentation over the last few years, I’m convinced that the diet-heart hypothesis is seriously off track.

As I continue this series, which you can follow on Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn (or by just bookmarking and checking in regularly), I’ll introduce you to authors, physicians and scientists who have influenced me toward that position, as well as to some of the stronger studies that have led me to adjust my personal behaviors.

Even if you reach a different conclusion, it’s good to have explored the arguments so you’re making dietary decisions consciously instead of by default.