Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating have been a huge part of my health journey and of Lisa’s, thanks to an introduction to the concept from Dr. Jason Fung.

When we tried 10 weeks of alternate-daily fasting, that was when Lisa really started to see impressive weight-loss results.

Now fasting is just part of our routine. As I’ve tracked with the Zero app, I have fasted at least 13 hours on 269 of the last 270 days.

Usually I have two meals a day, four to eight hours apart. Sometimes it’s just a single meal, a.k.a. One Meal A Day or OMAD, which is what Lisa typically does.

Occasionally we fast for more than 24 hours to accelerate autophagy and for cancer prevention.

I believe I first heard of the idea of fasting for cancer prevention through Dr. Fung, primarily in the context of how long-term caloric restriction has been demonstrated to increase longevity and to reduce cancer incidence, both in animals and in people.

But who wants to live like that all the time?

What if you can get most of the benefits of chronic restriction through periodic pulses of fasting, while eating normally the rest of the time?

That leaves the question of dosage: how long does the fast need to be, and how frequently do you need to do it?

The short answer is no one really knows, but here is why Lisa and I have settled on three days every other month.

I had heard about Dr. Peter Attia’s practice of a seven-day water-only fast (a.k.a. the Nothingburger) once per quarter as a potential cancer-prevention strategy, and so I decided to try a seriously extended fast for the first time about 15 months ago.

Instead of water only I also allowed myself coffee, and I went five days, from Sunday evening to Friday evening. I did another of these last February, but cut it to four days because my sleep quality the previous night hadn’t been good.

Meanwhile I heard that Dr. Attia had changed his personal practice to a three-day fast each month. It’s two more days of fasting per quarter, but spread out over three months instead of all at once.

As I said, no one knows the “right” dose and frequency, but this seemed like something worth trying.

In November and December I did three-day fasts. The slightly lower intensity than my previous 4-5 day fasts was appealing, but I still had that nagging question of whether it was enough.

Then I finally checked out some videos from Professor Thomas Seyfried (as highlighted in my last post) on the metabolic approach to cancer treatment through a ketogenic diet and related interventions.

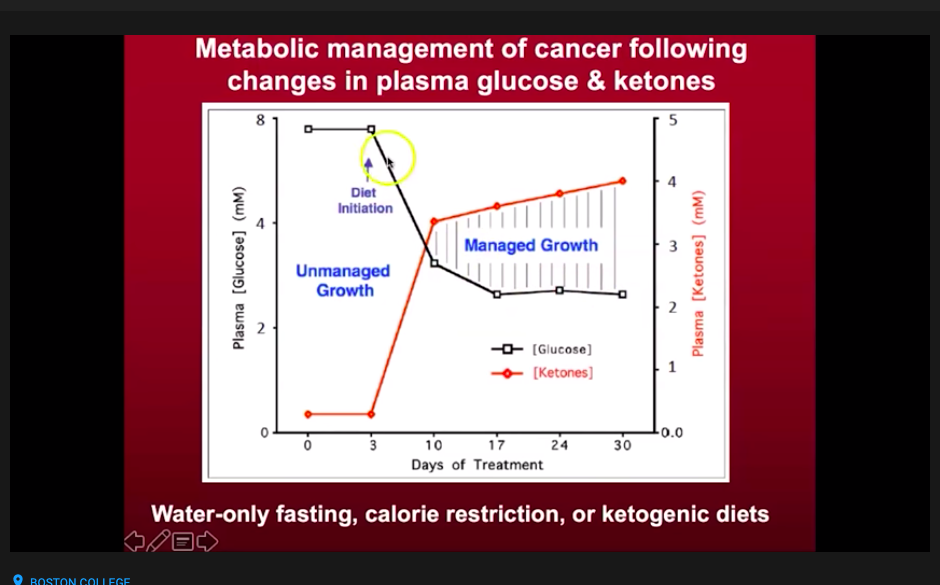

He described the glucose-ketone index (GKI) he had developed to measure whether patients were in an optimal, deep level of ketosis. A GKI of 9.0 or less indicates some level of ketosis, with 1.0 or lower being the highest therapeutic level.

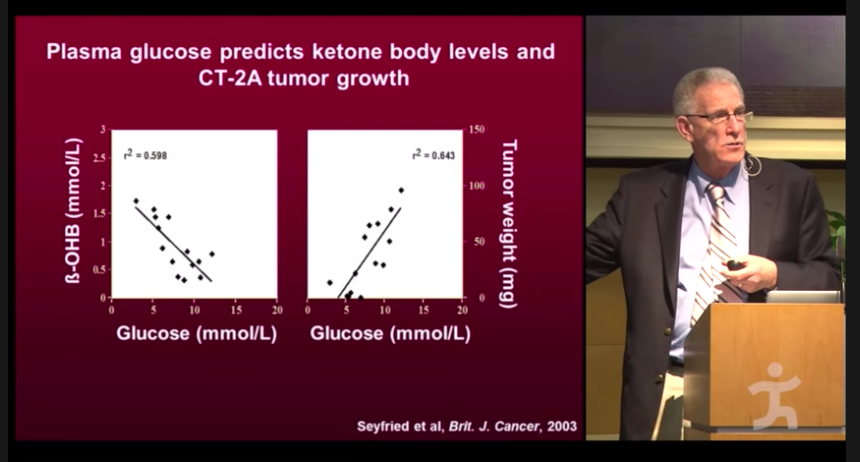

Increasing ketones and reducing glucose allows normal cells to thrive, while cancer cells – which lack the ability to use ketones for energy – are placed under stress.

I also was interested in confirming that my normal blood sugar levels weren’t masking an underlying condition called insulin resistance. If I had normal blood sugar levels only because my pancreas was cranking out lots of insulin, that would not be healthy.

I felt pretty confident that I had reversed any insulin resistance I may have had before my weight loss, but I wanted to confirm it.

Testing insulin levels is complicated and expensive, but I had learned that having ketone readings of 0.5 mmol/L or higher is a back-door way of confirming low insulin levels. They’re in a reciprocal relationship: elevated ketones aren’t compatible with high insulin.

I also heard someone mention the Keto-Mojo device that enables home measurement of blood glucose and ketones, and which enables tracking through a mobile app, so I took the plunge and got a starter kit for about $100.

My Keto-Mojo arrived the day after I started my December fast, and that evening my GKI was 3.2. By the 48-hour mark of my fast I reached 1.0 and I stayed below that (0.8, 0.5 and 0.5) until I broke my fast 24 hours later. I remained below 3.0, which is considered high-level ketosis, for another 24 hours. I maxed out at 6.2 mmol ketones with blood sugar at 61 mg/dL.

It seems that if GKI at or below 1.0 is the therapeutic target for those undergoing metabolic cancer treatment, being there for at least 24 hours once a month gives a reasonable chance of being helpful in cancer prevention.

It isn’t rock-solid confirmation for the three-day fast Dr. Attia uses, but it gives me some reason to believe I’m in a fasting range that should be beneficial.

I think Professor Seyfried put it well toward the end of the video I embedded in my last post:

These are non-toxic approaches. I can’t tell you whether it’s going to be the solution to the cancer problem. But I can tell you ‘I think it works, and it’s not going to hurt you. And it has the potential mechanistically to be very effective.'”

Thomas Seyfried, Ph.D.

Our next three-day fast starts tomorrow afternoon. This time I’ll be working to ensure I’m in ketosis before I start my fast, which should make it easier, and also will be taking GKI readings throughout the full fast instead of starting partway through the fast.

I’ll also explore strategies to get to that GKI ≤ 1.0 as quickly as possible to have the greatest therapeutic effect.

I’m not asking you to join Lisa and me in this fast, but if you’re curious I do invite you to follow along as I share observations on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

I’ll also write a daily recap post here that you can receive if you subscribe by email.

Check out My Health Journey for the full story of our health improvements, and my #BodyBabySteps for an approach to how I would do it if I were starting today, based on what I’ve learned.